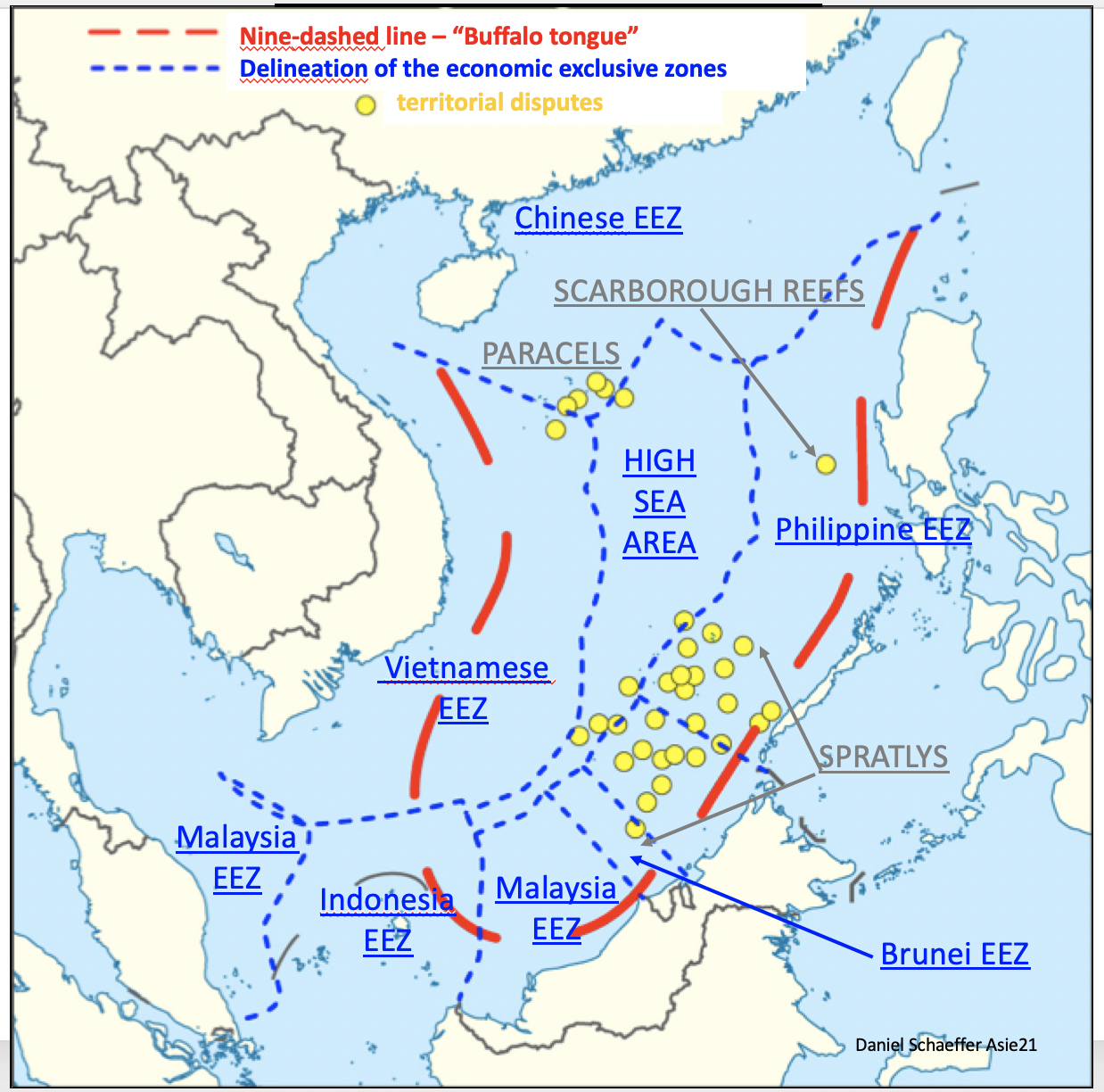

Map : Overlap of the South-East Asian nations’ EEZs by the « buffalo tongue »

By General (ret.) Daniel Schaeffer

Former French defense attaché in Thailand, Vietnam and China

Member of the French think tank Asie21[1]

Notice: This issue may be reproduced at will provided Asie21.com (www.asie21.com) is clearly quoted as the original source.

By continuing to negotiate a future code of conduct (COC) of the parties in the South China Sea, the South East Asian nations are preparing a situation worse than today in their relations with Beijing, at least as long as the nine-dashed line that borders the “buffalo tongue” over that sea has not been deleted. Explanation.

通過繼續就南中國海各方的未來行為準則(COC)進行談判,東南亞國家與北京的關係正在準備比今天更糟的局勢,至少只要舌形九段缐尚未刪除。

On the occasion of the 18th ASEAN-China Senior Officials’ Meeting on the Implementation of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) in the South China Sea, held in Dalat, Vietnam, on October 15, 2019, it appears that the participants in “the meeting had a full exchange of views on the second reading of the COC text”[1]. This means that the negotiations on the future code of conduct of the parties in the South China Sea are proceeding faster than it had been announced at the end of August 2019. The negotiations planned at that time were scheduled to resume in October, not on the COC itself, but on the Single Draft South China Sea Code of Conduct Negotiating Text. That means how much the ASEAN countries bordering the South China Sea appear to be in a hurry to elaborate a text supposed, but only supposed, to guarantee them, once finalized, some tranquility when, exerting their legitimate sovereign rights, they exploit their own respective exclusive economic zone (EEZ). That second reading will be, for sure, endorsed on the occasion of the next ASEAN summit and related summits to be held between October 31 and November 4, 2019 in Bangkok.

But beyond such an optimistic progress of the negotiations, some doubts are casting their shadows as far as the consequences could result when the COC is adopted and applied. It is what is suspected when Teodoro Locsin Jr, Foreign Affairs Secretary of the Philippines, met with former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on September 25, 2019. On that occasion, when he revealed that the first draft of the COC had been completed, he clearly expressed his concerns this way: « It is implicit recognition of China’s hegemony. In short, a manual for living with a hegemon or the care and feeding of a dragon in your living room ». A queer remark from a governmental authority at the moment when his president, Rodrigo Duterte, coordinator of the ASEAN – China relations until 2021, is so keen to reach an agreement quickly. But such a reaction coming from Locsin is quite revealing of the anxiousness that assails most of the ASEAN members’ minds.

So, with such a consciousness of what an excess of power a future COC would provide China against the riparian countries of the South China Sea, why are the negotiations continuing and are not suspended? Moreover after China created so many troubles to Malaysia in the area of Luconia breakers in May, when since last summer China continues exerting a lot of pressures over Vietnam on Vanguard bank, at the farthest southwest of Spratly islands, as well as on block 06-01, and for more than one year over the Philippines around Thitu island and Second Thomas shoal. If China is behaving that way today, it shall be worse tomorrow once the COC is adopted, at least as long as Beijing continues refusing to delete the nine dashed line, line denounced with “no legal effect” by the Permanent Court of arbitration on the 12th of July 2016, line which draws a “buffalo tongue” over that huge part claimed by China over the South China Sea.

If China today already considers that Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines are wrong when they exert their legitimate sovereign rights in their own respective EEZs but in sectors overlapped by the “buffalo-tongue”[2], if China today already considers those countries as treading on its own rights, then once the COC is adopted Beijing will consider them as trespassers and as such condemnable. But the situation will become worse for these presumed trespassers from the moment they will not be judged by an international court but will be judged by a Chinese one elevated to an international level, even though, once, China cautiously took to making clear that these courts shall be parallel to but not in replacement of the international ones already existing.

As a matter of fact, since 2010, some Chinese politicians are calling for a maritime law so that China may “protect” its “territory and settle boundary disputes with surrounding countries »[3]. Later, on March 10, 2016, Zhou Qiang, the chief justice of the People’s Republic of China’s Supreme People’s Court expressed, in front of the National Assembly, the ambition to create an international maritime judicial centre, without really explaining what would be the purpose of it[4]. Not much later, in August of the same year, it appears a little more clearly that the basic ambition was “a bid to turn China into an international maritime judicial center” [5], with all the present maritime judicial courts being directed to improve their capacities in international law, thus providing the Chinese maritime judicial system with an international authoritative voice.

Later, under this general idea, things are becoming a little bit clearer. On March 12 2017, Xinhua news, quoting a report of the Supreme people’s court, said that “China has extended its maritime jurisdiction to cover all seas under its jurisdiction in an effort to resolutely safeguard the country’s maritime rights and interests”. And “According to the regulation in effect since last August 2016, jurisdictional seas not only include inland waters and territorial seas, but also cover regions including contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones, continental shelves, and other sea areas under China’s jurisdiction. Chinese citizens or foreigners will be pursued for criminal liability if they engage in illegal hunting or fishing, or killing endangered wildlife in China’s jurisdictional seas”. Therefore here we are.

As a matter of fact, isn’t it clear enough that “sea areas under China’s jurisdiction” encompass the “buffalo tongue”? And in these conditions isn’t it deductible that the COC will open the door wide to Peking to let it, at its own will, sue the ASEAN country considered the culprit, although the latter will be exercising its legitimate rights in its own EEZ but in a part cut by the “buffalo tongue”?

At present it is amazing, except from very few observers[6], researchers[7], analysts, rare politicians such as David Stilwell, US assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs [8], jurists such as Filipino Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Tirol Carpio[9], who all are trying to ring the alarm-bell, to see how the ASEAN negotiators seem to turn a blind eye on this future danger. Even governments from the United States and Europe, which are calling for a binding code, seem to be quite unaware of that expectable Chinese behavior once the code is adopted.

As long as the nine dashed line has not been deleted, when the ASEAN countries continue negotiating a code of conduct of the parties in the South China Sea they are for sure weaving the Chinese rope with which they will be hanged. Do they really want to commit such a political and strategic suicide?

General (ret.) Daniel Schaeffer, Asie21

[1] The 18th ASEAN-China Senior Officials’ Meeting on the Implementation of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) in the South China Sea Successfully Held, Ministry of Foreign affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2019 October 16th, available at https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/wshd_665389/t1708862.shtml

[2] See map attached

[3] Zhao Yinan, Speed called on maritime law, China daily, January 11, 2013, available at http://www.nanhai.org.cn/en/news_detail.asp?newsid=4796

[4] See the analyses of:

– Susan Finder, China’s Maritime Courts: Defenders of ‘Judicial Sovereignty’, A closer look at China’s maritime courts and how they bolster China’s sovereignty claims, The Diplomat, April 5, 2016, available at http://thediplomat.com/2016/04/chinas-maritime-courts-defenders-of-judicial-sovereignty/.

– Shannon Tiezzi, China’s Plan for Lawfare in the Maritime Domain, “Lawfare” at work in the maritime domain, The Diplomat, 15 mars 2016, accessible à http://thediplomat.com/2016/03/chinas-plan-for-lawfare-in-the-maritime-domain/.

[5] China’s maritime jurisdiction extends to cover all jurisdictional seas, Xinhua net, March 12, 2017, available at http://www.xinhuanet.com//english/2017-03/12/c_136121825.htm

[6] The Code of Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea: a tremendous mistake, Asie21, August 17, 2017, available at https://www.asie21.com/2017/08/17/the-code-of-conduct-of-the-parties-in-the-south-china-sea-a-tremendous-mistake/; Mer de Chine du Sud – Code de conduite: Quand l’ASEAN prépare la corde chinoise qui pendra ses dix membres, Asie 21, September 19, 2018, available at https://www.asie21.com/2018/09/19/mer-de-chine-du-sud-code-de-conduite-quand-lasean-prepare-la-corde-chinoise-qui-pendra-ses-dix-membres/

[7] Huong Le Thu, The dangerous quest for a code of conduct in the South China Sea, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, July 13, 2018, available at https://amti.csis.org/the-dangerous-quest-for-a-code-of-conduct-in-the-south-china-sea/

[8] US warns of SCS code of conduct with China, Philippines Institute for maritime and Ocean Affairs, October 19, 2019, available at https://www.imoa.ph/us-warns-of-scs-code-of-conduct-with-china/

[9] Ralph Lawrence G. Llemit, Disputed sea code of conduct a ‘trap’, Sunstar Davao, October 23, 2019, available at https://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/1820129

當東盟國家繼續編織將吊掛它們的中國繩索

丹尼爾·謝弗(Daniel Schaeffer)將軍

曾任法國駐泰國丶越南和中國的武官

法國智庫Asie21的成員

通過繼續就南中國海各方的未來行為準則(COC)進行談判,東南亞國家與北京的關係正在準備比今天更糟的局勢,至少只要舌形九段缐尚未刪除。

2019年10月15日,在越南大叻舉行的第18屆中國–東盟中國高官,關於執行《南海各方行為宣言》的會議上,與會者似乎在“會議上對COC案文的二讀進行了充分的意見交換” [1]。這意味著有關南中國海各方未來行為守則的談判的進行速度,比2019年8月底宣布的進展要快。當時計劃的談判,計劃於10月恢復,不是在COC本身,而是在《南中國海行為準則談判文本單一草案》中。這意味著與南中國海接壤的東盟國家,似乎急於擬定文本,以便在行使其合法主權時,利用其各自的主權獲得一定程度的安寧,也就是開發各國的專屬經濟區(EEZ)。當然,在2019年10月31日至11月4日期間,在曼谷舉行的下一屆東盟峰會及相關峰會之際,將通過二讀。

但是,除了談判取得如此樂觀的進展外,在採納和實施COC可能產生的後果方面,有些疑問正籠罩著陰影。菲律賓外交大臣特奧多羅·洛辛(Teodoro Locsin Jr)於2019年9月25日與澳大利亞前總理陸克文(Kevin Rudd)會面時,就清楚地表達了他的擔憂:«這是對中國霸權的隱性承認。簡而言之,一本關於與霸主共同生活,在客廳中照顧和餵食龍的手冊»。當他的總統,直到2021年的東盟與中國關係協調員羅德里戈·杜特爾特(Rodrigo Duterte),如此渴望迅速達成協議時,這是一個政府機構的奇怪言論。但是,Locsin的這種反應,充分顯示了困擾大多數東盟成員國思想的焦慮。

因此,在意識到未來的COC,將為中國提供對抗南中國海沿岸國家的權力時,為什麼談判會繼續進行而不是中止?此外,在5月份中國在盧卡尼亞(Luconia)地區,給馬來西亞造成了許多麻煩之後,自去年夏天以來,中國繼續在南沙群島(西南)最遠的Vanguard沙洲以及06-01區塊對越南施加很大壓力,並在Thitu島和第二托馬斯淺灘周圍的菲律賓上空,超過一年。如果中國今天的行為方式如此,那麼一旦通過COC,明天將變得更糟,至少只要北京繼續拒絕刪除2016年7月12日國際常設仲裁法院曾“宣判不具法律效力”的舌形九段缐 。

如果今天的中國已經認為越南、馬來西亞、菲律賓在自己的專屬經濟區中,但在與舌形九段缐重疊時,行使其合法主權時是錯誤的,那麼一旦COC被採納,北京將視他們為侵入者,並應受到譴責。但是,從一開始,這些假定的侵入者將不會受到國際法院的審判,而是由被提升到國際水平的中國人來審判,這種情況將變得更糟,即使中國曾經謹慎地表明這些法院應與,但不替代,已存在的國際標準平行。

事實上,自2010年以來,一些中國政客呼籲制定一項海事法律,以便中國可以“保護”其“領土並解決與周邊國家的邊界爭端” [3]。2016年3月10日,中國最高人民法院首席法官周強,在人代會面前曾表達了建立國際化的雄心。

1 réflexion au sujet de « South China Sea: When the ASEAN nations are continuing weaving the Chinese rope that will hang them 當東盟國家繼續編織將吊掛它們的中國繩索 »

Les commentaires sont fermés.